Your Weirdness is Welcome Here

Letter from Eve Tushnet

A version of this letter from Eve Tushnet is featured in our anthology “A Place to Belong: Letters to Catholic Women”, a devotional that includes letters from 25 different Catholic women and explores the many different ways in which Catholic women are living out the feminine genius today.

Hey--

Back in 1998 or 1999, when I was a very recent convert to Catholicism and full of boisterous, somewhat obnoxious delight in the Church, I told my best friend that as a Catholic, “It’s just that my worldview is so unified!”

One of the great blessings of friendship is that she made fun of me for this for twenty years.

It can be easy to feel like the Catholic Church hands you an intricate, interlocking object, and if you handle it correctly, all the pieces fall into place and your faith forms a perfect and beautiful sphere.

This is a misconception which Catholics ourselves often buy into, when we suggest that our faith gives us “answers to life’s questions,” or that the great thing about being Catholic is that you will always have clear guidance in what to do.

But many of us find that we don’t have clear models for what we’re supposed to do—what it would even look like to bring all our wild, weird, harrowing experiences to the altar.

Especially if something in your life or your calling from God hasn’t been modeled for you by the Catholics around you, it can feel like you’re locked out of that small, perfect sphere of faith.

I spent about a decade and a half bringing my out-of-control drinking to the confessional and wondering why nothing ever got better. Some priests tried their best to give me good advice. One suggested inpatient rehab; another, more confident that he had my answers, told me I had to go to Alcoholics Anonymous every day for a week. I wasn’t sure if that was part of my penance, so I did it. One hour every day morbidly sucking on my hangover coffee, listening to people tell stories I was supposed to relate to and feeling nothing except, All these people are better than me. Which turns out to be the kind of thought you have right before you buy another bottle of bottom-shelf bourbon.

I’ve put together seven years of sobriety piece by piece, and if the pieces don’t seem to fit together the way they should, I don’t care. I love the 12 Steps; I still don’t do meetings. I started going to daily Mass (and then I stopped, and now I’m trying to start again). My experience of addiction was intensely spiritual (rather than, for example, psychological), but even when I’m talking with other people who needed what AA calls a “spiritual solution” it’s often easier to see the differences in our experiences than the similarities. It doesn’t matter.

God didn’t give me their recovery. He has as many different paths to hope as there are people in despair.

On a maybe less intense note, I have many friends who love Eastern liturgies, spiritualities, and styles of worship—some Orthodox, some in Byzantine or Melkite churches (which are in communion with Rome). I’ve loved learning from them about the diversity of Christian worship, the diversity of the beauty available to us, and the diversity of the languages we can use to articulate our faith. It turns out that I am desperately Western: gory Spanish crucifixes, St. Anselm on the Cross as payment of our debts, statues and holy cards and the Corpus Christi procession. One of my favorite memories of church music is of “Amazing Grace” played on a Casio keyboard—it should be so chintzy, and yet it was so haunting! And there’s probably no document from the Vatican explaining why that was so good.

The Faith is more complex and strange than any precision-tooled theology can express.

The kinds of Catholicism you were raised with aren’t the only kinds; the vocations of the people who brought you into the Church aren’t the only paths of love.

When I became Catholic, all the other Catholics I knew were straight. I didn’t know any other gay people who were willing to accept the Church’s sexual ethic. I didn’t even know of anybody like that. For all my talk of having a unified worldview, there seemed to be no place for me—and especially for my longing to love and serve other women—in the Church. I acted like being Catholic gave me all the answers, when in fact I wasn’t even sure how to ask the questions.

As a gay woman I have had to rediscover forgotten ways of love: Scriptural practices of lifelong same-sex love, for example, like the covenant between David and Jonathan or the promises made by Ruth to Naomi.

Both Scripture and Christian history offer examples of people whose love of another man or another woman was intense, devoted, and chaste; self-giving, life-shaping; passionate, sacrificial, and beautiful.

St. Gregory of Nazianzus describes his friendship with St. Basil the Great as being like “one soul in two bodies.” Their friendship, in which they rejoiced in one another’s progress in the spiritual life, drew each of them closer to Christ as well as to one another. St. Frances of Rome had an even more obviously life-shaping partnership with her sister-in-law Vannozza, who went to Mass with her, prayed with her in a secret chapel, and served the poor and imprisoned alongside her. Contemporary Christians—including many gay and lesbian believers—are reviving old Christian practices like covenants or blessings for friendship, finding ways to let their love of someone of the same sex be a pathway to Christ and not a barrier to following Him.

One of the great ongoing joys of my life in the Church has been learning how many ways there are for us to pour ourselves out in love. Marriage and religious vows aren’t the only Catholic forms of love, service, kinship or community, and if you need a different form of love—a different shape for your life and your future—you can be certain that God will help you.

There will be a path for you, even if it’s hidden, even if it takes a long time to find. Even if your Catholic friends or family find it very hard to understand.

Sometimes I still wish I could present my faith to other people as a perfect shining sphere. I still get embarrassed by my uncertainties, my weaknesses and failures (even though often it’s in these moments when I learn some humility, some compassion for others). I still get embarrassed by the thought that my life might not be enviable. I might want to be a good example, but I keep turning into a cautionary tale….

But again and again I’ve learned that other people need the rough edges, the weirdness, the unanswered questions and unslaked longings.

The perfect shining sphere can be inspiring—but it’s also intimidating. It’s hard to imagine being like those people whose faith seems to fit so easily into the grooves of their lives. (And honestly, those people often feel the same way. They don’t feel like they’re living a picture-perfect, #soblessed life!) The places where I’m still working out what God wants for me—including in my deepest friendships—are places where I “walk by faith.” They’re the places where I need to trust in God the most.

Catherine of Siena was a laywoman (everybody forgets this because she went around in a habit!) who counseled, “Build a [monastic] cell inside your mind, from which you can never flee.” She lived with monastic single-mindedness in the secular world. That’s one kind of contradiction. She also subjected herself to severe physical penances—but later in life she warned a nun away from harsh penances that get in the way of our loving service to God.* That’s a different kind of contradiction: a realization that you’ve tried to live a form of Catholic piety which might not have been right for you.

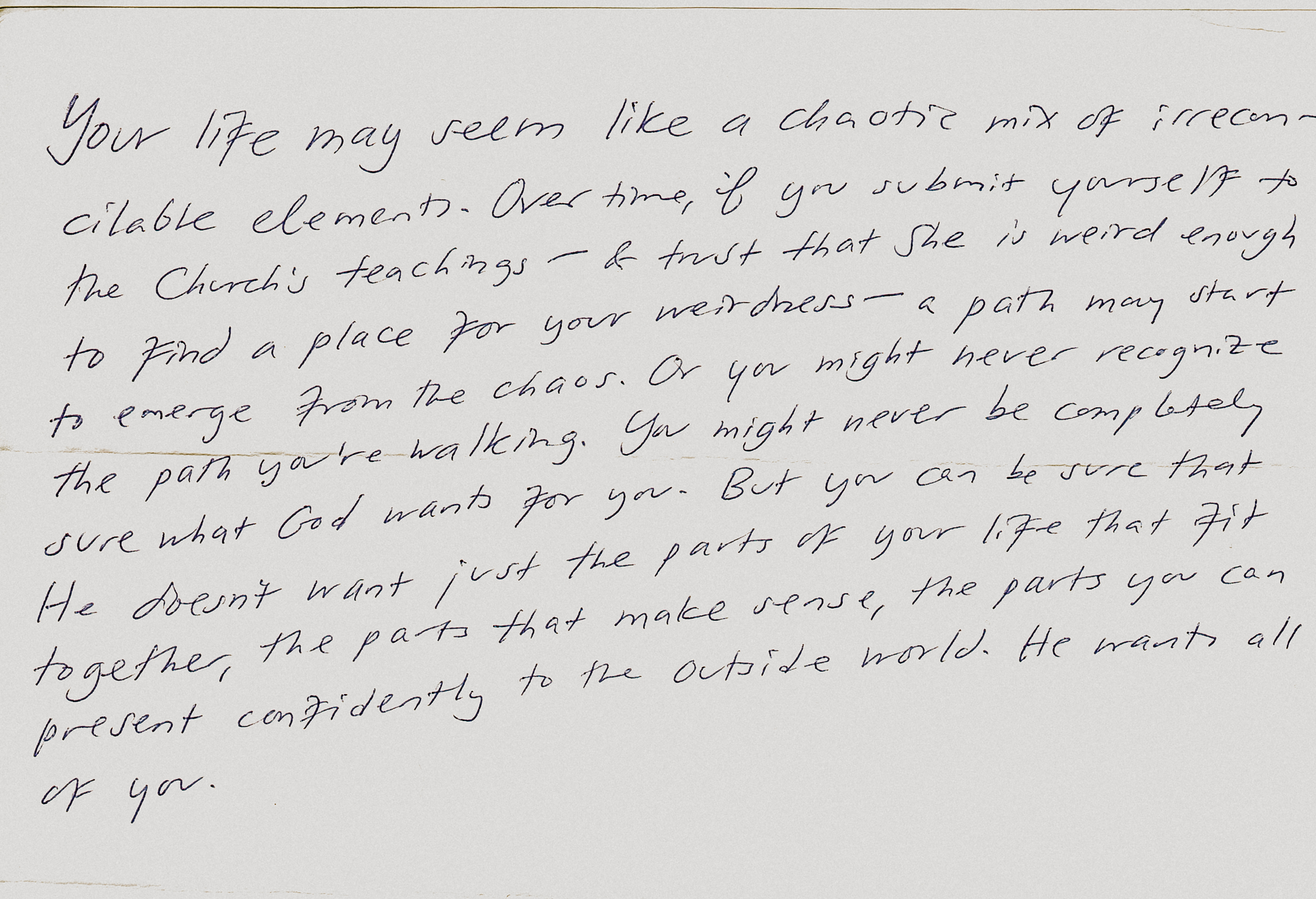

Your life may seem like a chaotic mix of irreconcilable elements. Over time, if you submit yourself to the Church’s teachings—and trust that She is weird enough to find a place for your weirdness—a path may start to emerge from the chaos. Or you might never recognize the path you’re walking. You might never be completely sure what God wants for you.

But you can be sure that He doesn’t want just the parts of your life that fit together, the parts that make sense, the parts you can present confidently to the outside world. He wants all of you.

In love and trouble--

ELT

Handwritten quote from the writer

*From ‘A Name Which No One Knows,’ an essay by Catherine Addington featured in the anthology Christ's Body, Christ's Wounds: Staying Catholic When You've Been Hurt in the Church

Want to share the quote below? On your smart phone: press, save and share.

About the Writer: Eve Tushnet

Eve Tushnet is a writer and speaker living in her hometown of Washington, DC. She entered the Catholic Church in 1998, at the ripe old age of nineteen. She is the author of Gay and Catholic: Accepting My Sexuality, Finding Community, Living My Faith and Amends: A Novel, and the editor of Christ’s Body, Christ’s Wounds: Staying Catholic When You’ve Been Hurt in the Church. She writes about everything from little-known punk movies to men’s figure skating, and from ministry to corrections officers to medieval penitential practices. Hobbies include sin, confession, and ecstasy.